I had seen this image for years in houses, in the fields in Latin America, and I remember something about a girl counting the toes or something like that.

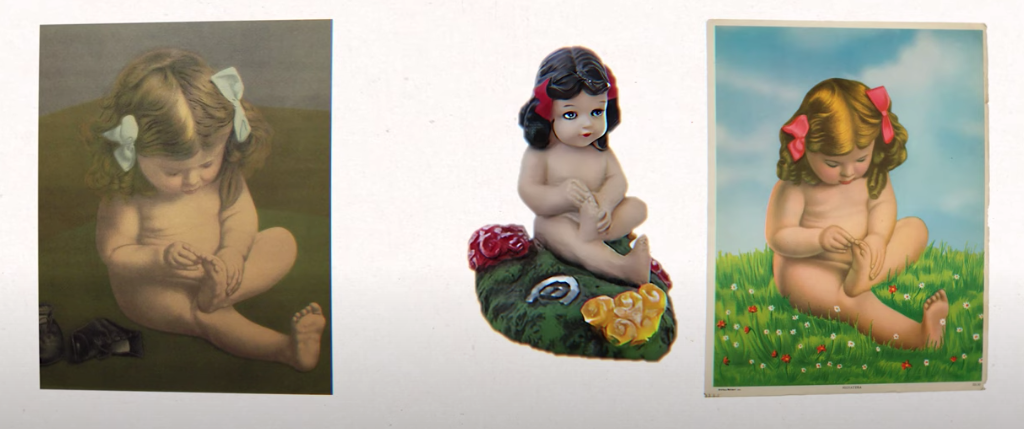

Naturally, my first instinct was to dive headfirst into the internet. And there was the image I had in mind, or so I thought, because studying this image led me down a rabbit hole of research and different names for the same painting: “Chubby Fingers” and “This Little Piggy.”

I realized that several antique dealers had different versions of it, but all seemed to agree that it was probably from the Victorian era, according to its style, at least from the 1900s. So it was about 30 years old or more. However, something in the back of my mind told me that this was not the image we were looking for. Right? I changed my search to Spanish, and there it was. This was the correct image.

But things got interesting. The two images, the one I found first and this one, look alike, but not quite, but yes, but no, but yes. And moreover, this image was not exclusive to the Dominican Republic, its presence extended throughout Central America, particularly to Costa Rica, and a new name emerged, a possible title for the image: “La Nigüenta.”

This revelation unleashed a slew of articles about the image, giving it a supposed origin and history, but the image is more than just an image. Because it was so widespread on all sides, it was already what we call today a meme, a shared experience. So I decided to ask you, to see what experiences you’ve had with this image. The response was overwhelming, and it revealed a spectrum of beliefs and theories.

Some suggested that the girl in the image could be a real person from Santiago, others said she lived in Barahona. Some of you even noticed a curious detail: the girl seems to have only nine toes on both feet. And besides that, several of you pointed out a series of recent articles in which the identity of the girl is revealed as Carmen Saleta de Ricard, a 98-year-old woman from Santiago who now lives in Miami. She even has a photo to prove it. So there you have it, the image is a copy of a photograph of this lady, except for the version of the image that supposedly is over 130 years old. I firmly believe in the idea that everything has already been investigated, and others much smarter than I have already studied this phenomenon, and that’s indeed the case; most of the research seemed to indicate Costa Rica as the origin of the image.

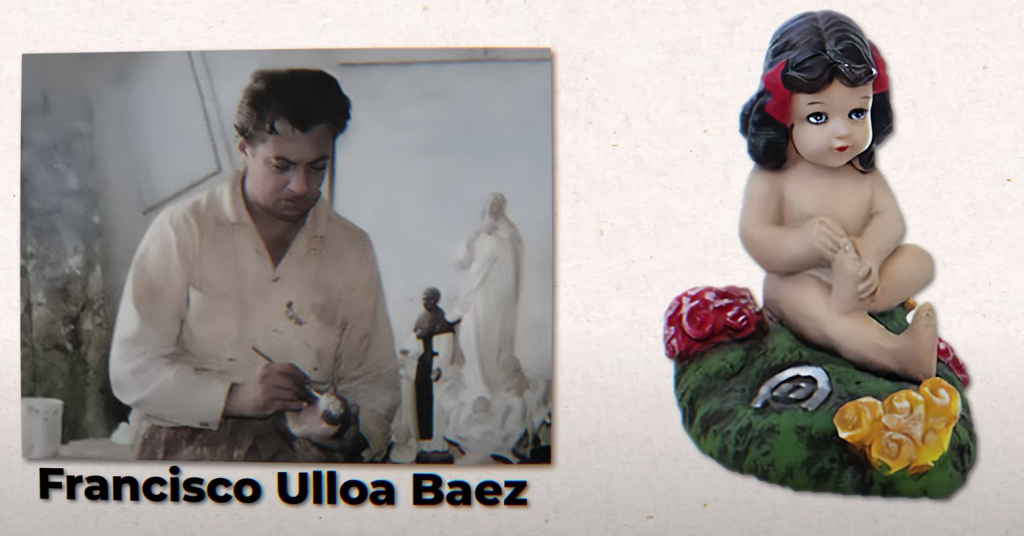

Costa Rica, the land of Pura Vida, bathed by two oceans, land of peaks, where people are characterized by their legendary cordiality and friendly nature, considered among the happiest in Latin America. But here, the girl was mainly known as a statue and had become a saint. An article from La Nación, a Costa Rican newspaper, tells us that Francisco Ulloa Báez, a sculptor from San Vicente de Moravia, is credited with creating La Nigüenta.

The story goes that in the 1950s, a friend’s business received a large shipment of artistic prints from Germany, including many of this girl. Noticing how quickly they sold, Uyoa was inspired to create a plaster version to sell at the Central Market of San José. The statue sold like hotcakes; the figure became especially popular in rural areas where religious items were also sold, such as statues of Jesus and statues of Costa Rica’s patron saint, the Virgin of Los Ángeles. But curiously, sometimes the girl sold better than the Virgin herself because a rumor arose that she brought good luck.

One of the sellers of this statue explains: “This was a very poor family, so poor that they didn’t have money to buy clothes for their children. Here, well, the little girl naked, she’s in the field taking off the “anigua“, the insect was like that in that position, seeing the finger, when she saw something shining on the ground. She picked it up, went home with the object she had found, gave it to her dad, and her dad, amazed, asked her where she had gotten that. It turns out it was a gold coin. They went to where the coin was, and they found a treasure there. That’s why we say La Nigüenta is for good luck.”

Attributing a story to an object creates reliability. But how did that story come about? Among other things, it’s pure speculation, but I dare say it was the street vendors and merchants who contributed. It’s a very common theme to attribute an inherent quality to a product to sell it better because personal conviction plus emotional connection gives us belief. And that, in turn, leads to sales. This works especially well when people are already predisposed to superstition.

Here we pray to La Nigüenta, huh? The one that doesn’t count. Some say that the tendency of rural Costa Ricans to believe in lucky charms originated in the indigenous practice of attributing magical properties to objects and figures, mixing these indigenous customs with the Christian tapestry, resulting in trends such as the veneration of La Nigua alongside Jesus and the Virgin.

So there, you can put the saint of Juárez and then the one of the Virgin and a woman arrives like me, at your house, then we could put it like La Pura in Radita, there was a little table, a receiver, and what they say, “Ah, we put it here,” but my neighbor put it on La Pura’s side. The little plaster doll quickly became a sales hit, which led Ulloa and his team to produce several versions and incorporate symbols of good fortune such as a horseshoe, a four-leaf clover, and the number 13.

It is said, according to tradition, that you have to put ribbons on it: red is for success and love, yellow is for money, white is to keep away a bad neighbor, and blue is for health. You can also offer it offerings. Every new year, you put a red sachet filled with grains so that there is no shortage of food throughout the year, and you can add some coins. Soon, other artists and even manufacturers in China began to produce their versions, extending La Nigüenta’s fame beyond Costa Rica’s borders, especially to Panama, Nicaragua, but also Honduras, Colombia, and other places. Today, it is difficult to find a house in Costa Rica without a La Nigüenta. It became an essential figure of Tico culture, especially because it was said to only bring good luck if one received it as a gift. Therefore, it is customary even today to give a La Nigüenta when visiting someone.

However, this only explains the plaster dolls of the girl, not the painting. Yes, it’s interesting to note that the plaster figure is sitting on the grass, with yellow and red flowers, just like in the painting. However, I couldn’t determine which inspired which. Although if we superimpose the image of the grass on the Victorian image, we can see that it is an exact copy, except for the color of the ribbon and the toes of the feet. In the Victorian one, she has 10 toes. It is possible that this image emerged at the same time when the original images ran out, while Ulloa decided to create plaster figures, someone else painted their version of the image to copy it. What is not clear is whether it was a Costa Rican or Dominican painter, because it turns out that the original appeared in both countries. In fact, almost all the images that became popular in Dominican houses also became common in Costa Rica and other parts of Central America, indicating that there was a great trade in postcards from Europe to Central America in the 1950s.

These prints reached rural areas through street vendors. These merchants brought art directly to the homes of peasants with only a limited selection available. The girl, in particular, had a unique charm that caught the attention of many and is still popular today, inspiring other artists. But who was the original artist then? The artistic style of the original version seems to be a form of illustrative realism popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, often used in images created for mass reproduction, such as postcards or commercial prints of the time. Thanks to printing advances, it became possible to print illustrations in bulk and sell them at low cost. Thus, prints and postcards were produced in large quantities and exported worldwide, facilitating the dissemination of images of places, art, and events. For example, it is thanks to postcards that we still have old images of Santo Domingo, such as the Colonial Zone.

The truth is that many artists struggle financially, and the business of postcards and prints became a welcome source of income, although it was not considered major art. It helped them pay rent and food. However, these prints and postcards were reproduced and copied so extensively that the artist’s name often got lost in the process. Unfortunately, none of the versions of the work that I managed to find bears the artist’s name, making direct identification impossible. Therefore, I could not determine the name of the responsible artist, and believe me, I spent a good time looking for it. But if the work apparently has its origins in the Victorian era, what about the old lady some claim to be the girl in the image? Well, it is said that this lady, Doña Carmen Saleta de Ricard, is no less than 98 well-lived years old, but the image dates from the early 1900s, from Europe, about 130 years ago. So, with all due respect to Doña Carmen, she is a bit too young to have been the muse of this piece. Also, that photo she has looks more like a postcard of the original work, boots and all.

Now, we haven’t had the pleasure of hearing her story, but putting together the historical crumbs that she was the muse is not quite right. All I can say is what several of you mentioned in the comments, that it was very common for parents and grandparents to claim that the image represented their children, and many grew up believing it. But there’s a persistent question, whether it’s the painting or the statues: what exactly is the girl doing? Well, it all depends on the context. The original image, with the line inside a house, with boots by her side, has been called different names: in English, like “Chubby Fingers” or “This Little Piggy,” in reference to a nursery rhyme. Another name, in French, that I found, calls it “Taking a stone out of the shoe.” But the narrative changed with the change of the image’s background. In a Dominican context, it could be seen as if she were pulling out a thorn or a stone from her shoe. But in Costa Rica, the story took another turn: the interpretation leans towards the girl removing niguas from her feet, parasites that were a common threat in coffee-growing areas of Costa Rica. Hence, she’s called “La Nigüenta,” directly linking her name to the flea, the chigger.

So, she’s counting her toes. She’s pulling out a thorn. She’s removing a flea. She’s taking a stone out of her shoe. Personal context influences our perception of art, and speaking of art perception, why is this artwork so popular? Because, let’s be honest, if you’ve ever felt that this image doesn’t reach what we’d call fine art, you’re not wrong. You may have noticed that in Latin America, there is a tendency towards this type of art, whether in painting, music, or entertainment: art with a focus on superficial feeling and not artistic mastery.

There is the philosophical concept of alienation. It is the idea that in our system, one ends up feeling disconnected from meaningful life experiences, creating an emotional void. The picture of the kid enters this void subtly, accessible, and doesn’t demand much from its audience. Unconsciously, it skips the head and goes straight to the heart. It’s just entertaining and touches our basic emotions, which is all we want to feel in this crazy world.

Let’s take our girl in the picture, for example. Because, let’s be honest, you’ve looked at her without caring about artistic mastery, but for her innocence, the way she sits without worries, absorbed in a simple moment. It’s the vibe she transmits, peaceful, pure, and somewhat lucky. That feeling, that’s what stays with you, and that’s why many of us still remember this image. It’s about that moment of connection, the universal desire to find a little serenity in our own lives, because it’s as if we’re all in a crazy race constantly. The world is, as always, in fast forward, pushing us when we’re still trying to learn to count our own fingers.